Thank you to those of you who have been here since day one. If you are new, I welcome you with open arms! This newsletter sprang forth from my tender love for latchkey kids and our surprising and sometimes disorienting stories. Each newsletter is my ritualistic approach to introducing you to the extraordinary inhabitants of Latchkey Township. I want you to treasure each one of these charmers as much as I do.

Today’s letter rings out with delicate grief and is painful to write.

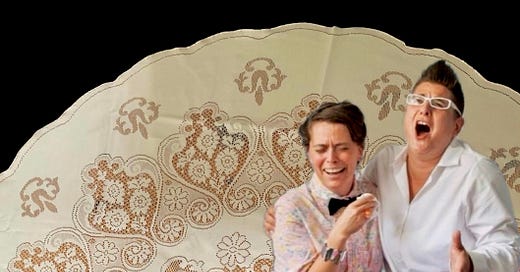

Julie Novak was among the first to contribute to Latchkey Township. From the moment I told her I was putting the book together, she was sooooo excited for all of us. She also spontaneously jumped up to MC the book launch when I suddenly felt too anxious after being verbally accosted by the host of the reading. This is what your very best friends do. They stand by you through unimaginable storms, gently easing the umbrella out of your shaky hands to hold it high up over your new perm.

With an agonizing heaviness in my heart, I share with you that Julie passed away on August 31. To say I miss her terribly is an understatement. When I get in the car and turn on the radio, a song or two during my drive inevitably reminds me so much of her. Maybe she sent these songs to me, I think. Sometimes, it is that peculiar song only she and one other person knew I listened to on repeat when I was four years old, a dying man’s farewell song to his loved ones, a song you just don’t hear on the radio anymore. It’s altogether too weird. And thus, most of my drives are spent weeping these days.

Julie created and hosted the first-class podcast No One Like You. I recommend a deep dive into the splendid universe Julie dreamt up, where each guest was mined for their unique inner gems, which she then tended to and displayed for the world to celebrate.

THE STORY OF US

At a barbecue twenty-five years ago, a charismatic stranger volunteered to remove a match-sized splinter from my butt. A dangerously large piece of wood from the deck had torn right through my shorts. I was quickly ferried into a bedroom in tears, with three close friends and this new dedicated and enthusiastic volunteer, who I assumed must be a nurse or doctor because of the level of confidence she exuded. I pulled down my shorts in front of this person I had only just met, and soon, my tears reorganized into peels of laughter as she completed the “surgery.”

I fell in love instantly. The term for falling in love with someone who saves you is "limerence" or "romantic gratitude" due to the emotional bond formed during a life-saving experience. My limerence for Julie Novak is irrefutable and eternal. Getting to be her friend since that day twenty-five years ago has been one of my life's most significant windfalls.

My friend Dexter sent me this old photo of us, which I hadn’t remembered, and I noticed the tiny word “music” in the upper left-hand corner of the image. It is as if the photo contains a time capsule secret message about how she might speak to me.

Without Julie’s physical presence, I am having difficulty finding my footing. I cannot picture my life without her. She was a sunbeam breaking through a shady grove when I felt sad. She was my creative collaborator for spontaneous and prankish adventures, but also for projects that took years to execute. I feel poached of the plan we had to grow old together, pulling our underwear into wedgies to make each other laugh well into our nineties. She was my intimate friend, my tourmate, my housemate, my confidante, my ex, my adopted sibling, my editor, and my sit-on-the-couch-each-week-and-tell-me-how-you’re-doing friend. She was someone I worked things out with again and again, even when it got hard, even when it felt like we wanted to walk away. She held an executive post on the upper deck of my chosen family. I want nothing more than to go back and rewrite this story and give it a different ending.

Julie Novak always stood firmly rooted in love for everyone, her family, my family, your family (even if she met them just once), her friends, strangers at the supermarket and airport, queer kids, trans kids, and even people who acted like assholes. She was dedicated to seeing the good in everyone and quietly promised to begin from a place of compassion no matter what. The closest glimpse I have to solace right now is imagining her beyond the veil, potentially now authorized to wave around a very important magic light baton, pushing, pulling, and influencing some mysterious knobs of power with her gigantic, loving energy force.

A friend recently offered the wisdom that the self Julie mirrored back to me is the self I must keep tending, protecting, and nurturing. I find this an interesting way of looking at the death of a loved one: attempting to live each day by trying to see yourself as they saw you.

In an instant, it feels as if the best carnival I’ve ever been to has suddenly packed up, taking my favorite clown with it. In the middle of a cloudy day, the carnies drove out of town before the sign on the telephone poll suggested they would be leaving. And now, I wake up each day and try desperately and frantically to find out where the next stop on the carnival circuit is. The rides have all been dismantled, and I feel only a kind of sickness, like I took way too many rides on the flying swings. My search leads me back to the fairgrounds. I look around the empty lot where the games, bandstand, funnel cakes, and enormous stuffed orange bears were, not knowing what I expect to find. And I begin to notice wisps of blue cotton candy gliding gently across the empty gravel parking lot, alighting on one tiny glistening stone after another before floating up to the clouds and mixing in with one of those sunsets that leaves you stunned. It is then I understand that she has left pocket-sized pieces of herself for us to find everywhere.

My mind is a pinball machine of memories. The complexities of our relationship could fill the Love Boat. We even had a song about the Love Boat when we started a band once, although I didn’t know the first thing about playing music. But that didn’t matter to Julie. She just handed me the mallets to the glockenspiel and infused me with confidence. With Julie, finding new ways to enjoy life was effortless, barreling at it full-speed and at top-volume. In the last year of her life, Julie would come to the vintage mall where I had a booth and spend hours making “commercials” with me. It was just another excuse for us to act like we were in fourth grade. Leave us alone for a few hours without parental supervision and see what happens.

When my friend Elizabeth Mitchell learned that Julie was in Hospice, she said, “I can't stop thinking about the first time I met Julie. You brought her to a school performance, and it was like we were all, in an instant, infinitely cooler than we had been an hour earlier because she was there, and she loved what was going on, and we all became realized beings through her radiant presence.”

Julie was my go-to date to see my students, former students, family members, and all the kids I once babysat in their plays, rock shows, and recitals. We shared a commitment to supporting the young people in our lives, and Julie was eagerly ready to beam with me at their talent and charisma. We would hold hands and cry in auditoriums and were always the first to give obscenely loud and long standing ovations. You could count on us to be the most embarrassing audience members if you dared invite us to your play.

Julie never belittled or condescended to anyone; she just honed in on your idiosyncrasies and made you feel as if those parts of yourself were memorable, pure, and even delightful. It was such a special gift of hers. Julie would gently pluck out a vulnerable part of you for closer examination, instantly conjure a way to help you find joy in that part of yourself, and then turn it into a ten-year-long inside joke.

I read a piece of writing on grief by Jessica Dore that said, “To lose someone of enough import to experience grief is to endure a rupture of normalcy. Mourning is responding to loss – often creatively, sometimes wildly – perhaps even to a degree that one is transfigured in the process and no longer fits inside pre-loss life structures. To really take in an absence is to risk becoming other than what one has been. It involves a willingness to be disoriented, at least long enough to be changed by what one has seen, experienced, and come to know.”

I know I don’t feel normal right now. I do feel deeply ruptured, different, and changed by this tremendous loss. I know that I will be disoriented for some time as I inspect my life for traces of her and question what my existence may look like without her. A grief of this magnitude will transform me in ways I cannot fully anticipate just yet. I promise to protect communal creativity and playfulness by offering them as anthems to Julie Novak.

“You tell lesser friends and tolerated family that you can’t even know what it felt like being you before Bob was your best friend. They give you a look when you say this. You ignore their looks. They just don’t get it. A person who hasn’t earned the friendship of a Bob is as thin as an incomplete sentence. Again, you never say this, but that doesn’t stop people from hearing it. Everyone knows you and Bob are a package deal.” —Saaed Jones.

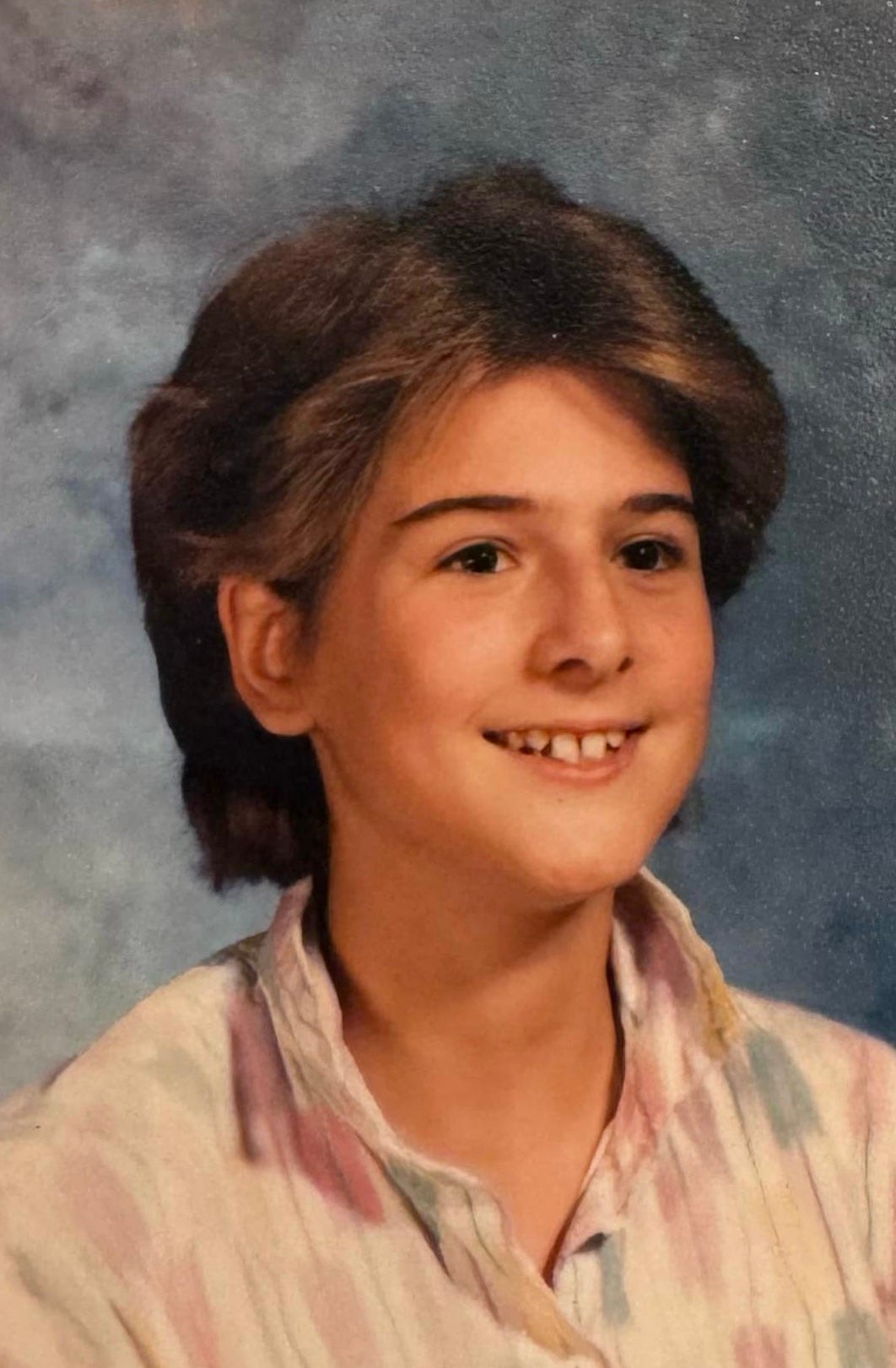

THE CARKEY KIDS

by JULIE NOVAK

I wasn’t so much a latchkey kid as I was a carkey kid. My mother would bring my brother, Steven, and me in her little orange Volkswagen Bug convertible as she drove from business to business, selling ads for our small-town paper, The Record-Courier. “Don't get out of this car,” she would command, leaving us with a giant bag of Brach's pick-your-own candy — an unlimited sugar buffet — as we waited for her, sometimes for what seemed like hours, to close the deal.

I don’t know if we ever broke the rules. I don’t remember ever leaving the car. I just remember being stuck in that cramped backseat for long periods of time, hoping that when we arrived at the next stop, we could finally get out. I don’t think I ever really understood what she was doing or that maybe it was not a good idea for us to be tagging along. It was cheaper than a babysitter, and we certainly didn’t have extra money.

I don’t think we understood, a bit later, that it was also not such a good idea for her to bring us to The Brass Frog in the middle of the day while she swilled Rusty Nails. At least we weren’t carkey kids anymore, but someone should have taken away hers. Even when we were with her, there were many times when we still felt alone.

Most of what I write here is free to read. That said, if you are excited to support my work or wish to pay me for the excessive hours I spend looking things up on powerthesaurus.org, I humbly accept your monthly subscription with the deepest gratitude.

Thank you, as always, for reading. Hug and call your friends. Tell them you love them fiercely. Don’t ever let go.

Have you ever lost a best friend? How was it different than other losses? How did you cope? How do you keep their spirit alive in you? Please let me know in the comments.

xo, Jacinta

“No one will remember us like I will remember us.” 🤍

That was beautiful. So sorry for your loss.